Great writing is all about rhythm. Glenn Stout, editor of the “Best American Sports Writing” series, has always known that, but the point was driven home to him in a long-ago conversation with the late W.C. Heinz, the writer who in his lifetime gave us the seminal 1949 piece “Death of a Racehorse,” a wonderful book about the Lombardi Packers called “Run to Daylight” and a host of other things.

Heinz, Stout told me over the phone last week, was a classical music devotee. And when he sat down to write, he might as well have been taking his place before a Baby Grand.

“Once he found the right chords and the right time signature,” Stout said, “well, then you just have to stay there.”

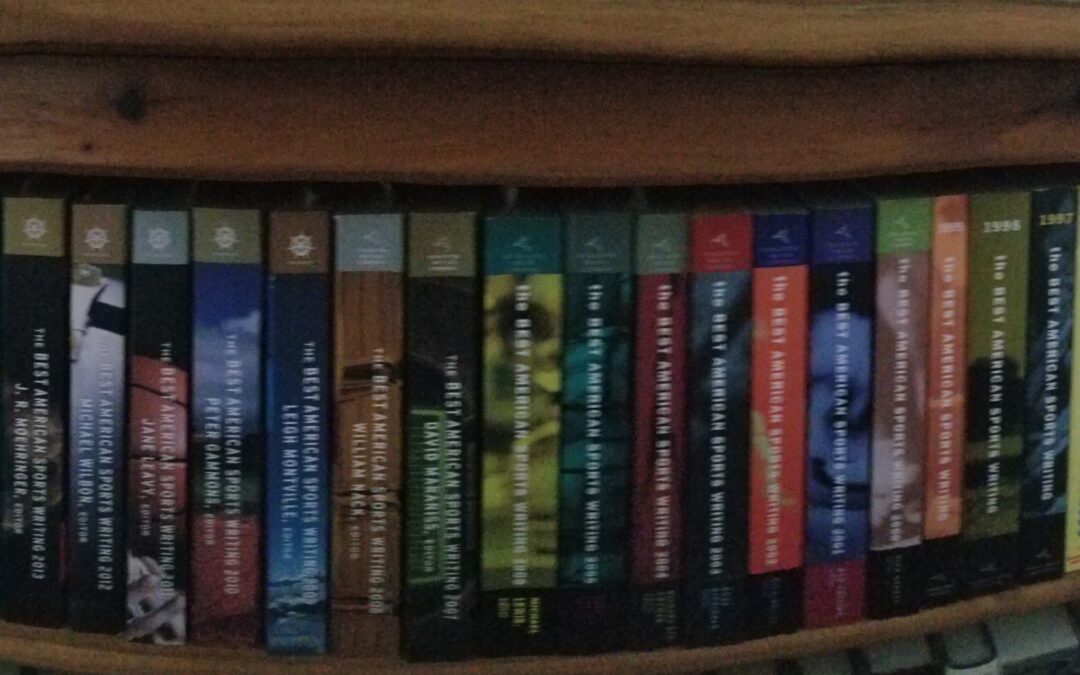

It don’t mean a thing if you ain’t got that swing, right? And if pieces like those produced by Heinz have a distinctive rhythm, so too have each of the last 30 years of Stout’s life. BASW’s point man since its inception in 1991, he began receiving submissions each January at his home in Alburgh, Vt., some five miles from the Canadian border. By his estimate there were about 10,000 of them in any given year.

He whittles that down to 75 pieces, which he forwards to that year’s guest editor — always an industry luminary — for review. The guest editor pares that to 25 or so for the finished product, which appears each fall.

While the 62-year-old Stout, an accomplished writer and author himself, must also attend to his own projects, he has become synonymous with BASW, having shepherded the series from the first book (which began with “Pure Heart,” William Nack’s story about the legendary racehorse Secretariat) to the most recent one (which ended with “Whatever Happened to Villanova Basketball Star Shelly Pennefather? ‘So I made this deal with God’ ” by Elizabeth Merrill).

Things are, however, about to change. Not quite a year ago the publisher, Houghton Mifflin, informed Stout that it was discontinuing the series — that the current edition, released Nov. 3, would be the last. The notification came by email, which admittedly left him “a little miffed,” as he put it.

“Thirty years of something,” he added, “maybe a phone call would be better.”

Sales had dropped off a little in recent years, he said, but not precipitously. He had some thoughts about how things could be changed up a bit, but he says nobody ever asked. And just like that, the final chapter ended, in every sense.

He’s not necessarily sad. He’s still immersed in the trade; his book “Tiger Girl and the Candy Kid,” a tale of a 1920s gangster couple scheduled for a March 2021 release, will be the 100th he has written, co-written, ghostwritten or edited. He also still talks with writers, still coaches them, still cares deeply about the craft.

“So it really hasn’t left a hole,” he said. “It has left a smaller pile of stuff in the corner of my living room.”

And while he is admittedly “a little cagey” about the topic, he said he is “very optimistic” about the series being revived in different form. He noted that BASW was preceded by a series called “Best Sports Stories,” and that together they spanned 75 years.

“I can say with some confidence that in the 76th year there will be another book,” he said. “I hope I’ll be somewhat involved — probably not as involved in the long term as I am with this one. But I’m pretty confident.”

Stout came by the BASW gig in 1990, through a bit of serendipity. He was eight years into his job on the research desk at the Boston Public Library by then, and four years into his career as a freelance sportswriter. He had also hired an agent, as he was looking to write a book.

His agent heard from someone else in the field that Houghton needed a sportswriter to edit BASW, and recommended her client. Stout was asked to assemble a collection of stories that might be found in such a book, which was hardly a problem for him, considering his full-time job and the fact that he had read so many entries in the “Best Sports Stories” series.

That got him in the door. Once hired, he recommended that “Sports Writing” — two words — be part of the title, as opposed to “Sportswriting,” since the idea was to highlight the writing, not necessarily the sports. It was, he believes, “probably the smartest decision I ever made with the book, and maybe the only decision I was ever allowed to make with the book.”

He also recommended that David Halberstam be the first guest editor, as Stout had come to know the famed author while he was researching his 1989 book “Summer of ‘49” in the Boston Public Library. Halberstam, who died in 2007, almost bailed early in the process, but ultimately saw it through, beginning a stretch that saw, shall we say, the best and the brightest follow him in that role: John Feinstein … Buzz Bissinger … Richard Ben Cramer … Rick Reilly … Dick Schaap … Charles P. Pierce … et al. ESPN.com’s Jackie MacMullan serves in that capacity in the series’ final book.

Stout moved with his family from Massachusetts to Alburgh in 2003, and the yearly routine continued: The submissions rolled in, and he hunkered down. Truth be told, he didn’t read every word of every piece; rather, he would read “until I think there’s a reason not to read anymore.” Sometimes that means reading the lede and skipping to the kicker at the end.

“Or,” he said, “I might read until I read something that tells me I don’t need to read anymore. I really tried to react almost viscerally to it as a reader. Because the reader is going to read it. They have one shot at it. It better work for me in that one shot. If I have to work too hard, if I see something that’s too mundane, that I’ve read 100 times before, well, there’s no need for me to read the rest of it.”

If that is the case, the submission winds up in the bigger of two piles in Stout’s living room — the one reserved for rejected material — and, eventually, his woodstove.

“It’s cold up here,” he said. “We need all the kindling we can get. There’s no value judgment on that: Thank you for contributing to our heating supply up here.”

(As an aside, I’m quite certain I’ve written something that has provided him and his family warmth. So it goes.)

There have been times when writers have lobbied hard for their work, and one occasion where a scribe was so insistent about a piece being included that Stout had to get an unlisted phone number. And while certain writers have made the cut more often than others — Gary Smith, late of Sports Illustrated, had the most entries over the years (13), and another gifted long-form writer, Wright Thompson, contributed 12 — Stout has always been open-minded.

“I’ve tried to just make sure to the degree that I can that everybody knows that everybody is welcome in this book,” he said, “and I’m not making prejudgments based on who you write for, or how old you are, or anything else.”

(As an example of this, Mark Pearson, a former Intell Sports part-timer and now the director of the Humphrey Family Writing Center at the Hill School in Pottstown, had a piece included in the 2011 edition of BASW entitled “The Short History of an Ear,” a first-person tale about wrestling, family and coming of age.)

Certainly there are some pieces Stout holds near and dear to his heart, like the aforementioned “Pure Heart” and Bill Plaschke’s “Her Blue Heaven,” about a disabled Dodgers superfan. But his was an ongoing search for pieces that had the right rhythm, the right feel. Time and again, that search bore fruit. And if his own personal rhythm has been thrown off for the time being, let the record show that it’s only a temporary thing — that the beat can be expected to go on.

I just read this post today, and I wish I had seen it back in November. Every year I wait anxiously for BASW to appear. I am not so much a sports fan as I am a BASW fan. The writing pulls me in. When I read the forward of the 2020 edition (the forward and the introduction are my favorite parts) and saw that BASW had come to an end, I started ranting. I had been anticipating some great writing about sports during the pandemic. I am so relieved to see that Mr. Stout will be bringing out a new collection in 2021. Saved!