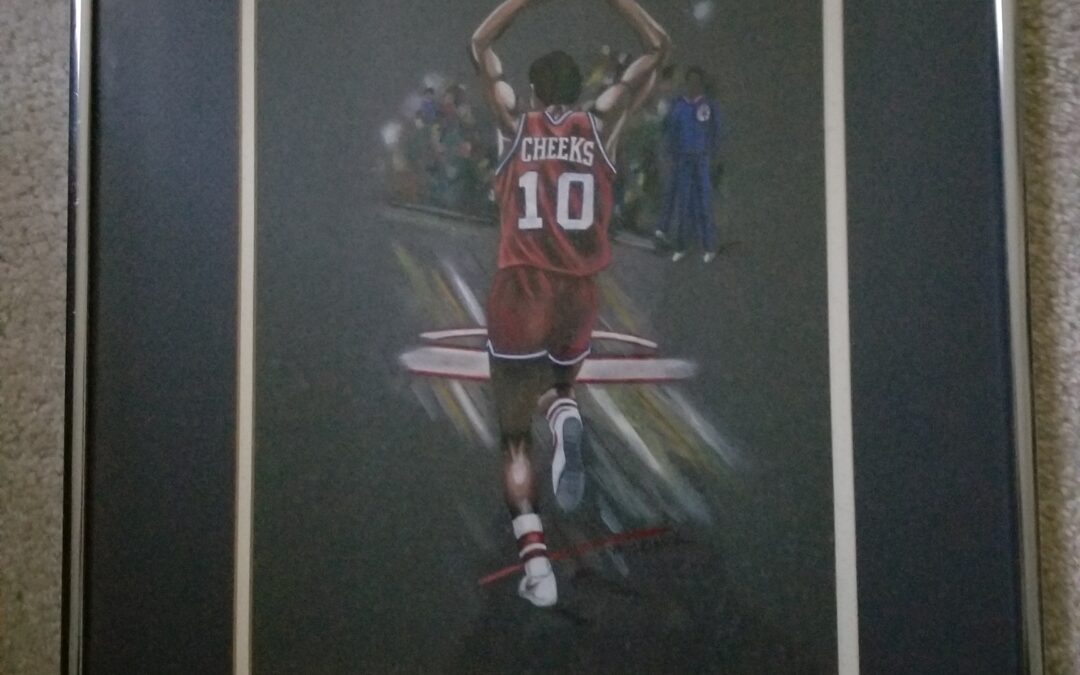

Since 1993 I’ve had the above painting on my wall, one adapted by a local artist named David Kirsch off a black-and-white newspaper photo I shared with him.

I love the subject and the symbolism — how it shows Sixers point guard Maurice Cheeks, a guy who seemingly never dunked nor showed emotion on the court, doing the latter after doing the former, as he and his teammates wrapped up a Game Four victory and a sweep over the Lakers in the 1983 Finals.

It remains the Sixers’ most recent championship, and Cheeks’ uncharacteristic celebration has always struck me as the perfect exclamation point — a workmanlike player letting loose in the moment, knowing how long the climb had been, and how much backsliding there had been along the way.

So the question now becomes this: Can you picture a similar scene being duplicated by the current incarnation of the team, in a season fractured by a deadly virus?

There are small parallels. That ‘82-83 team rose out of the ashes of a 9-73 season a decade earlier, while this one bottomed out at 10-72 in 2015-16 — the difference being, of course, that the ‘72-73 Sixers cratered because of managerial incompetence, the ‘15-16 outfit because they were Trusting the Process.

Certainly there was some luck to both rebuilds. The title team benefited from the dissolution of the ABA, which gave it a crack at Julius Erving. The current team benefited from the bounce of the ping-pong balls, which gave it a crack at Joel Embiid and Ben Simmons — the whole idea behind Sam Hinkie’s teardown to begin with.

The final piece to the ‘82-83 puzzle was Moses Malone. The final piece to the ‘19-20 Sixers was, uh, Alec Burks? Glenn Robinson III? Shake Milton?

Again, it’s not a perfect comparison, and never will be — in no small part because the rest of the season will be contested in a fan-less arena in Orlando, Fla., while the NBA plays Katy-bar-the-door with COVID-19.

The Sixers, 39-26 when the season was suspended in mid-March, resume Saturday against Indiana, the team with which they currently share fifth in the East. There are seven more regular-season games, then the playoffs — virus permitting.

This is unprecedented, but it’s always difficult. The old-time Sixers reached the very precipice of a title in 1977, ‘80 and ‘82, losing in the Finals each time. But they kept pushing the boulder up the mountain, kept gathering assets — a Hinkie word. Only difference was, they kept them.

In 1978 they drafted Cheeks at No. 36 overall (i.e., right after Marvin Johnson, John Rudd, Harry Davis, Greg Bunch and Tommie Green). That same offseason the Sixers traded George McGinnis, a great player in decline, for Bobby Jones.

Two years later they selected Andrew Toney eighth overall in the draft. The Nets had the two previous picks. They took Mike O’Koren and Mike Gminski — decent NBA players (and the latter a future Sixer), but not bad asses like Toney, who was Hall of Fame-bound until his feet gave out in the late ‘80s.

(Two favorite memories of Toney. According to legend, the first time he entered Boston Garden, he was trying to find his way from street level up to the arena when he said, “Where the gym at?” I love that he reduced this most hallowed of NBA cathedrals to a mere gym — and then treated it as such, torturing the Celtics at every turn. Speaking of which, it was my distinct pleasure to inform M.L. Carr that the Sixers referred to him as “Lunchbox” when I was working on a story about Toney last year, because Toney always ate his lunch. Carr, the ultimate provocateur in his day, didn’t seem pleased.)

Then Malone arrived, and the puzzle was complete. He was brought in by owner Harold Katz, a Trumpian figure forever eager to take the credit when things went well but never accepting of blame when they went sideways — as they would later in Katz’s tenure. (He traded no fewer than three future Hall of Famers — Cheeks, Malone and Charles Barkley. He also drafted Shawn Bradley.)

Moses came at the expense of Caldwell Jones, a player beloved by his teammates for his selflessness. After the Sixers won it, Billy Cunningham actually offered CJ his championship ring. Jones demurred.

(This tragic side note: Jones, Malone and Darryl Dawkins died within a year of each other, beginning in September 2014 — none older than 64, and all from heart-related issues. And in April of this year another Sixers center of that era, Mark McNamara, also succumbed, at age 60, to a cardiac issue. When I asked about this seeming epidemic recently, neither Pat Williams, the team’s general manager from 1974-86, nor Joe Rogowski, the NBA Players Association’s Director of Sports Medicine, could hazard a guess as to why this might be so. But Rogowski said he and his staff are on the case.)

The upshot is that everything fell into place for those long-ago Sixers. The current edition hasn’t had to pay as many dues, but neither is the window likely to stay open as long as it did back then, given player movement and such. So if this is their time, so be it.

What we know is that Simmons has really, really worked on his 3-point shot, and while this strikes me as a Lucy-with-a-football situation — haven’t we been down this road before? — he at least showed a willingness to fire in the first scrimmage, against Memphis. The bigger news is that he is now playing power forward, which makes sense from every angle. He will still handle the ball, particularly in the open court, but in halfcourt situations there will be another shooter on the floor, notably Milton. And Shake, the 54th pick in 2018, seems to be another in a string of gems the Sixers have unearthed in the latter stages of recent drafts (Matisse Thybulle — via trade — as well as Furkan Korkmaz and the departed Landry Shamet being other examples).

Of course there are red flags, the latest a calf injury that kept Embiid out of Sunday’s scrimmage against Oklahoma City. But the goal remains the same as it was, all those years ago: creating an ending that’s suitable for framing.

And that’s never easy.