Any self-respecting media type entering the locker room of a pro basketball team knows the drill: You speak to the stars out of obligation, the lesser lights out of interest.

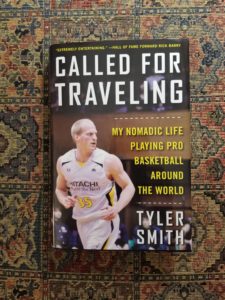

An Everyman – a guy like Tyler Smith, for instance — is more relatable, more self-aware, more like the public at large. And if it is a pleasure to approach him, it is even better when he approaches us, as was the case with the recent release of his diary Called For Traveling (Sports Publishing).

Smith, a 6-8 forward and 2002 Penn State graduate, played professionally for 11 seasons, ending in 2013. Spent time in Holland and Uruguay, Argentina and Italy, Japan and Thailand – not to mention stateside, in the NBA Development League. Twelve teams in all, on three continents.

He began his career as a single guy, and ended it as a married father of two daughters. (He and his wife Cara, who live in State College, have since become parents to a third daughter.)

He and his burgeoning family survived a magnitude-9 earthquake that killed thousands in Japan, and his on-court career had its share of aftershocks as well. He injured no fewer than nine body parts, ate strange foods (like cow’s blood, in Uruguay) and had to badger shady management types for the money he had earned on more than one occasion.

During an injury-induced interlude he also coached under the late Armen Gilliam, the second pick in the 1987 NBA draft (and a guy who played 13 seasons, including two-plus with the Sixers), at PSU-Altoona. And at his final stop (in Thailand) Smith was coached by none other than Joe Bryant – i.e., Kobe’s dad, and another ex-Sixer.

So yes, this Everyman seemingly experienced everything.

Smith relates it wonderfully, in a 363-page memoir marked by humor and self-effacement. The book is, by Smith’s own admission, not as edgy as Can I Keep My Jersey? the 2007 diary written by another journeyman, Paul Shirley. But that was bound to be the case, as Smith is a deeply spiritual man.

His work stands on its own merit, however, as does his career. Playing 11 years of pro ball is no small achievement, no matter the location.

“It’s just such an unorthodox, different lifestyle,” Smith, now 38, said over the phone recently. “It’s really fun and stressful and uncertain, kind of all at the same time.”

That he stuck with it is no small point of pride for Smith, who said Shirley’s book was an inspiration to him. And after friends marveled at the experiences he related via email early in his career, he finally set out in 2013 to write a chapter a month over the course of that year.

“My little New Year’s resolution,” he said, “one I actually kept.”

He had been no less persistent as a player, weathering an Achilles tear, broken nose, shoulder dislocation, knocked-out tooth, cut cheek, back spasms, eye poke (twice), rib contusion and, uh, groin injury.

“When you list them out like that,” he told me, “it’s like, gosh. Everywhere I went, something would happen, inevitably.”

He never had a fear of injury, but did worry as to whether he would get adequate care. He was not about to have his Achilles tear, suffered in Uruguay three years into his pro career (in 2004-05), repaired there; rather he returned to the States for that, and rehabbed at Penn State.

As for the earthquake, it occurred in March 2011, when he was playing in Japan, and stands as the worst to ever strike that country, and the fifth-worst ever. Over 15,000 people lost their lives, and while it was happening Smith was left to ponder his own fate.

“To be that violently shaken, it’s such a weird feeling,” he said. “You just kind of feel like, oh my gosh – it’s the end of the world.”

He was on the eighth floor of a Tokyo hotel at the time, having hunkered down with his teammates before a game. They were able to make their way to the street, but it was an anxious time for him, as he could not reach Cara. She was, along with the couple’s eldest daughter, Hannah, an hour away, in the city of Kashiwa, where his team was based.

Finally he learned they were safe, if only relatively so. There would be aftershocks “like every 30 minutes,” he said. There would be tsunamis along the coast.

He marveled at the way the skyscrapers in Tokyo withstood the quake, marveled even more at the way the people dealt with the calamity. There was no rioting, no looting, no chaos.

Rather, he said, “People were just like, ‘Oh, I’m grocery shopping. We just had an earthquake. I’ll go put all my stuff back, because the registers are down. We’ll help other people.’ They’re so organized and such honorable people, it really just kind of blew me away.”

That extended, frustratingly, to his team. When the players finally made their way back to Kashiwa, their coach convened a practice, believing the season would be resumed. Smith, appalled, went through the motions until word came that the league would in fact be shut down for the year.

He had crossed paths with Gilliam years earlier, after the Achilles tear cut short the ’04-05 season. Met him, he said, when he was walking to dinner with Cara along a street in Altoona and Gilliam drove up. Having seen his height, he asked Smith if he played basketball.

Why yes. Yes, he did.

Gilliam wondered if he might be interested in helping out, and Smith agreed to do so. He found the older man to be an engaging guy, but as Smith added, “He didn’t always maybe seem super organized.”

One day, Tyler said, he asked Gilliam about breaking down film.

“He’s like, ‘Man, this is D3. We don’t need to do all that stuff,’ ” Smith said. “He just loved the game, but wasn’t maybe the greatest coach in the world.”

Gilliam, who played in the NBA from 1987 to 2000, reserved his energy for other pursuits, like one-on-one or racquetball. He was always up for a game, Smith remembered. Made his death, at age 47 of a heart attack (sustained during a pickup hoops game in 2011 at a Pittsburgh-area health club), that much harder to fathom.

“He was so healthy,” Smith said. “That’s what blew me away.”

Bryant was full of life, too. The man once known as “Jellybean” spent eight years in the NBA (1976-83) – the first four with the Sixers — and eight more playing in Italy, and has been a long-time coach overseas. When his team was short-handed for a tournament during the 2012-13 season, he also suited up and played alongside Smith, at age 58.

Bryant then proceeded to outscore him.

“I think I even took a picture of the boxscore; I have it somewhere,” Smith said with a laugh. “And I was like, ‘There it is, man. … It might be time for me to hang ‘em up, because a 58-year-old just outscored me.’ ”

So he did retire. These days he owns a cryotherapy company and sells medical devices, while playing in an old-guy league.

“There’s refs and a scoreboard, and neither one of them are right,” he said. “At least it’s better than the treadmill.”

His body feels good, he added, better than it ever did while he played. And his memories are something to savor.

They are also best when shared, as he proves in these pages.