When the Baltimore Orioles last won the World Series, all the way back in 1983, the decisive blows in their decisive Game Five victory over the Phillies were struck by their glowering first baseman, Eddie Murray. Murray homered twice that day off Charles Hudson — that Charles Hudson, as Harry Kalas and Richie Ashburn likely called him in subsequent years — the second a prodigious two-run blast to right field that threatened to go right through a Veterans Stadium message board en route to Camden.

Cal Ripken Jr. was on first base at the time. He dutifully tagged up.

He informed me of this one August day 15 years ago, as we sat within Ripken Stadium, in his hometown of Aberdeen, Md. The place — dubbed Cal Sr.’s Yard in honor of Ripken’s late father, an Orioles lifer — serves as home park for the Aberdeen IronBirds, an O’s Class A affiliate partially owned by the younger Ripken. It is surrounded by a youth-baseball complex consisting of miniaturized versions of Wrigley Field, Fenway Park, Nationals Park, Yankee Stadium and Memorial Stadium.

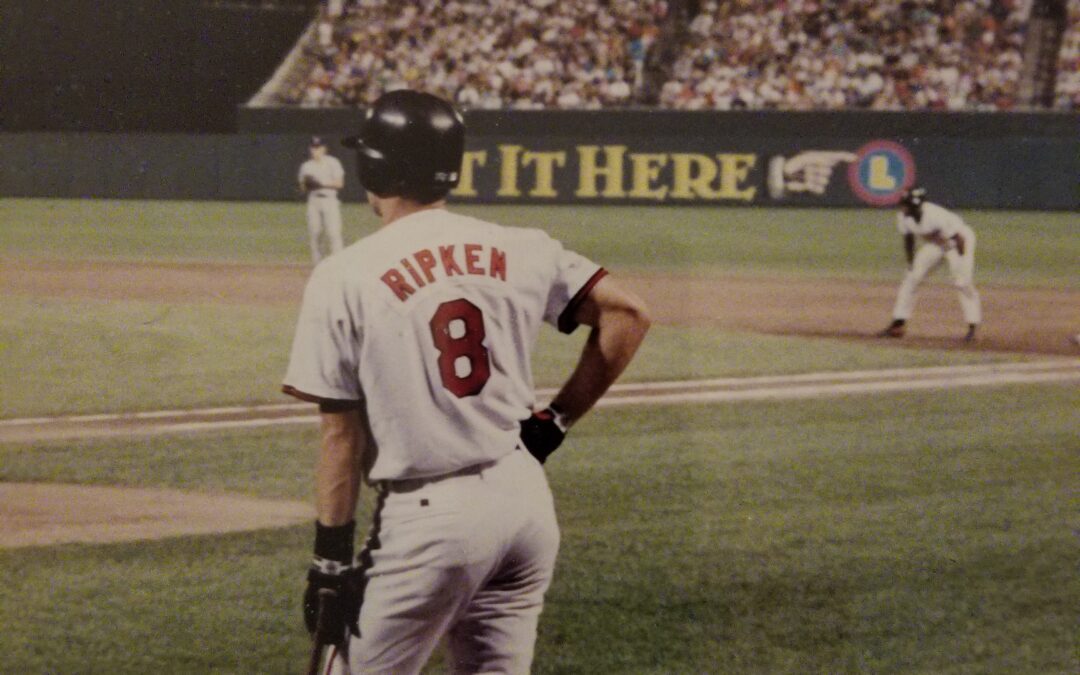

I had come there to discuss him surpassing Lou Gehrig’s storied consecutive-games streak 10 years earlier, a streak Ripken would eventually extend to 2,632 before finally resting in September 1998. We wound up talking about little things, like tagging up when Eddie Murray scalds a ball halfway to Ho Ho Kus. Or when Ripken made the final outs in Memorial Stadium by grounding into a double play on Oct. 6, 1991, sealing a loss to Detroit.

I covered both those games, and marvel still at Murray’s blast. Officially measured at 425 feet, it struck the message board as it was listing the American League RBI leaders — specifically, right above the “M” in Murray’s last name, as he drove in 111 runs that season to finish fifth.

Quite a punctuation mark, that.

Certainly, though, I didn’t recall Ripken tagging up — an act, he admitted, that earned him untold grief from his teammates. Nor do I remember the Memorial Stadium finale. Ripken, however, could cite chapter and verse. How in the latter case Frank Tanana was pitching for the Tigers (wait — Frank Tanana pitched for the Tigers?) and it was late afternoon, making it difficult to see the ball. And how that resulted in a defensive swing and an around-the-horn twin killing.

So maybe that’s the best way to view The Streak — for all the tiny little moments that comprised it, as opposed to its enormity. They’re the things that make baseball so fascinating anyway, whether you’re talking about a pitcher missing his spot by a fraction of an inch, a hitter catching one on the sweet spot as opposed to the end of the bat or a fielder playing someone here, as opposed to here.

And Ripken, who passed Gehrig by playing in his 2,131st straight game on Sept. 6, 1995 — a 4-2 victory over the Angels that came 25 years ago, as of last Sunday — excelled at those little things. That might not make him the most compelling figure in baseball history (his homers in No. 2,131, as well as Nos. 2,129 and 2,130, notwithstanding). But it does make him the ultimate grinder, in a sport that demands as much of its participants.

Certainly there were times during The Streak, which ran from May 30, 1982 to Sept. 20, 1998, when its worth was questioned. When Ripken was viewed as selfish and his pursuit of Gehrig meaningless. So he went to work every day, the 9-to-5ers said. Who among us doesn’t do that? But that misses the point. So too does the assertion that Ripken does not belong in the same breath as the Iron Horse. While Gehrig is undoubtedly a legend, I would submit to you that the gap between the two is not as great as it might appear, given the fact that Ripken came along after the sport was integrated and cross-country travel had become the norm. (Moreover, Ripken, a shortstop most of his career, played a more demanding defensive position. And while he hit a modest .276 during his 21-year career — to .340 for Gehrig — he did eclipse 400 homers and 3,000 hits, typical Hall of Fame benchmarks.)

On the other hand, there is Ripken’s oft-stated belief that if a manager wanted to sit him, he reserved the right to do so. But that too seems disingenuous. After The Streak reached a certain point, no skipper had enough juice to hold him out. Ripken’s pursuit had grown bigger than the team, bigger than the sport, bigger than anybody and anything. It would have taken extraordinary guts (or extraordinary reasoning) for him to be pulled, no matter who was filling out the lineup card.

So he plowed on and on. Dan Connolly of The Athletic noted recently that Ripken overcame knee, ankle and back problems at different points in The Streak. And as for the criticism, he argued to Connolly that continuing to play was “a little bit more unselfish than selfish,” that in his mind he was allowed to continue on because he “brought value to each and every day.”

Which brings us back to all those tiny little things — things Ripken had learned from his dad, who briefly managed the O’s, and served the organization in a variety of other capacities over the years: If there was a game, you played. If you played, you tried to do something that spilled the outcome in your team’s favor, no matter how subtle.

In his case, you understood your responsibilities beyond the field as well. As he grew ever nearer to Gehrig, Ripken would stage impromptu postgame autograph sessions, standing on the field next to the home dugout and signing for fans who had queued up in the lower stands of Oriole Park at Camden Yards. I witnessed one such session after a loss to Toronto in August 1995. The line extended all the way back to the main concourse, and the fans came bearing every item imaginable. One woman even asked Ripken to sign her shoe.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “I didn’t come prepared. Just sign to Patty: ‘P-A-T-T-Y.’ ”

Ripken signed for some 90 minutes in all, ending at 12:25 a.m.

“It’s not a big deal, I guess,” he said before ducking back into the clubhouse. “It’s easy to sign your name. It’s easy to meet, greet and talk to people. And you find out you know most of them out there. It’s fun. It’s nice. The time passes very quickly.”

A quarter-century later, we’ve found out just how true that is in a larger sense, too. How for all that has happened since — Ripken, now 60, has weathered a divorce and cancer scare in recent years — it seems that it was just yesterday that he took a lap around Oriole Park to celebrate passing Gehrig, dapping up fans as he went.

A big moment, no doubt. But really, Ripken was all about all the small ones. The ones that make all the difference in his chosen sport.