Vacationed in Hawaii for the first time recently, with my wife and some friends. Did the luau thing, the whale-watch thing, the beach thing and the volcano thing, and one day did the Oahu thing, too. Flew there one morning from the Big Island and clambered aboard a van for an eight-hour loop of the island that would take us to Pearl Harbor, the North Shore (site of many major surfing competitions) and Waikiki, as well as a half-dozen other places.

Six other passengers were already aboard the van when it pulled up outside the airport – a family of four from Idaho, and two women from Southern California. (That, admittedly, sounds like the set-up line for a joke: Four Pennsylvanians, four Idahoans and two Californians get into a van …)

And then there was the driver/tour guide, a 23-year-old man. As we went about our day and got to talking with him a little bit, somebody noted his sturdy build and asked if he might have played a little football somewhere along the line.

Turns out he had. Just not as much as he might have hoped.

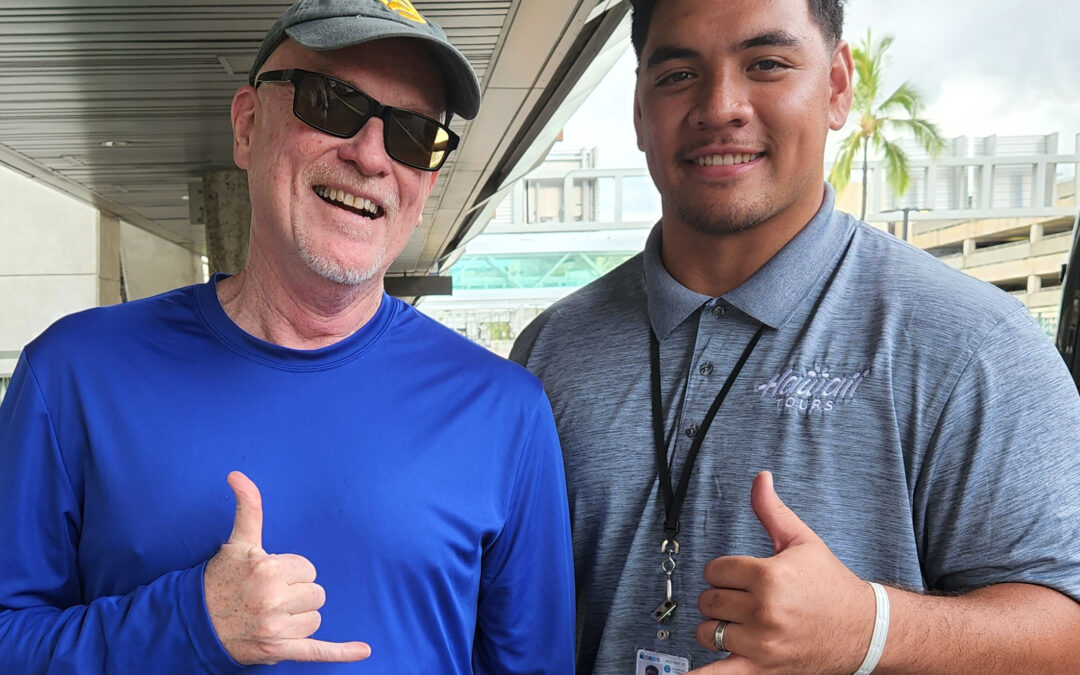

Kesi Ah-Hoy, born on Oahu to Samoan parents (and pictured above, with yours truly), had in fact been a two-time all-state player at Kahuku High, a school on the North Shore that has produced 25 pro football players (20 of whom played in the NFL or the old AFL, the rest in the CFL, USFL and Arena League) and won nine state championships. He was an integral part of one of those title teams, in 2015, rushing for nearly 1,300 yards and 18 touchdowns as the quarterback in a run-heavy offense. The following year he played safety and after initially making a verbal commitment to the University of Hawaii opted instead for Oregon State, where he was moved to inside linebacker.

His college career lasted five games.

On Sept. 30, 2017, Washington visited Oregon State. The Huskies, headed for a 10-3 finish (including a Fiesta Bowl loss to Penn State), were good. The Beavers were not. They would wind up 1-11, and see their coach, Gary Andersen, resign in midseason.

Ah-Hoy had carved out a special-teams niche for himself as a true freshman, to the point that he was the “off” returner on kickoff returns – i.e., more likely to serve as a blocker for the primary returner, but seeing the ball every now and then.

He would see plenty of work that day; the Huskies rolled to a 42-7 victory. And it was on one kickoff return that his fortunes were forever altered.

“What I remember was just running through a gap and just sticking my head into a guy’s chest, and then, boom,” he said.

He first believed he had suffered a stinger – a stretching/pinching of the nerves in the neck, which causes a burning sensation – only this was more severe than any he had ever suffered before. For 10 or 15 minutes, he said, he couldn’t so much as lift his left arm.

“And then,” he said, “it went on for the whole next day and I couldn’t even lift a gallon of milk.”

He visited one doctor, then another and another, and they all told him the same thing: The nerve damage in his neck and shoulder was such that a similar collision could result in permanent paralysis. They recommended that he give up the game.

Not what he wanted to hear. He said his grades sagged for a time, that he “just didn’t want to do anything.”

His mom, Mona, and his high school coach, Vavae Tata, set him straight, made him understand that he would have to find a new direction. And in the meantime the coaches at Oregon State vouched for him, even amid staff upheaval. After Andersen departed following the Beavers’ sixth game in 2017, assistant Cory Hall served as interim coach the rest of the season. He was then replaced by Jonathan Smith, who agreed to honor Ah-Hoy’s scholarship and allow him to serve as a student assistant coach.

“It was just one door closing and another opening,” Ah-Hoy said. “Football’s not everything, and football does have an expiration date, like milk, right? And so you’ve got to accept that one way or another. The faster you do, the more you can get on with your life – make something of it, instead of dwelling on it.”

And in fact life started coming at him like an unblocked edge rusher. He married his girlfriend, Lilia Kaka, in March 2020 – right after COVID-19 hit the U.S., meaning they were limited to 22 wedding guests. The following spring he completed his coursework, albeit virtually, and earned a degree in human development and family services. Not long after, in May 2021, he and Lilia welcomed a daughter, Porowini Ali’tia, into the world.

While serving as a student assistant he had considered pursuing a career in coaching, but then realized the demands of the job are such that those in the profession are “time-broke,” as he put it, and never able to settle down in any one place.

“Which is not what I want,” he said.

So he took the job as a tour guide and dispatcher, while also working a masonry job on the side and operating a business he describes as a “mini-Amazon” with Lilia, peddling toothpaste, shampoo and the like.

He proved to be a terrific guide – warm, funny and knowledgeable. Also prideful. Every now and then he talked football, notably as we wheeled past his school, which including the intermediate wing houses some 1,399 students in grades 7-12. Minutes later he steered the van into a neighborhood where a flag was flying that listed every year Kahuku had won a state title.

“Football is like a religion here,” he said.

That’s true of a great many small towns, in a great many parts of the U.S. But few have seen 25 guys go on to play professionally. The school’s alums include the Kemoeatu brothers, Chris and Ma’ake, who won Super Bowls with Pittsburgh and Baltimore, respectively, and Aaron Francisco, who played in one with Arizona. (His team, in fact, lost to Chris Kemoeatu’s, in February 2009.)

The first Samoan to play in the NFL was Al Lolotai, in 1945. He is a Kahuku grad. So too was the late Leo Reed, who followed up his brief pro career – he played only in 1961, with Houston and Denver of the AFL – by becoming a longtime Hollywood labor leader. (Reed died in February of this year, at age 83.)

Two other Kahuku products, Itula Mili and Chris Naeole, enjoyed NFL careers of a decade or more – Mili as a tight end with Seattle, Naeole as a guard for New Orleans and Jacksonville. Both played in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

There is also a Penn State connection to the school. Tim Manoa, a fullback on the Nittany Lions’ 1986 national championship team (and later an NFL player himself), attended Kahuku from seventh through ninth grades before transferring to North Allegheny High, in Wexford, Pa.

Many have considered the question of why men of Samoan heritage are more likely to play in the NFL – 40 times more likely than those born elsewhere, according to something Rob Ruck, a professor of transnational sport history at the University of Pittsburgh, wrote in August 2019. Over the years they have included Hall of Famers like Troy Polamalu and the late Junior Seau, and currently they include Chiefs wide receiver JuJu Smith-Schuster, Patriots wideout Kendrick Bourne and Dolphins quarterback Tua Tagovailoa. (Tua played at Saint Louis School in Honolulu, which Ah-Hoy described as Kahuku’s “archenemy.”)

Ruck noted that the population of American Samoa, a U.S. territory in the South Pacific, is 55,000, and that another 180,000 people of Samoan descent live in the U.S. According to Ruck there have been, in recent years, about 50 players of Samoan descent in the NFL – three percent of the league – which, again, is 40 times more than there are in the general population.

He cited theories such as the socioeconomic conditions in American Samoa, as well as the fact that Samoans eat a diet featuring a starchy vegetable called taro – the “Samoan steroid,” it is sometimes called – which accounts at least in part for the bulk of many of those who have gone on to play professionally.

Ruck also mentioned that those of Samoan descent live by “Fa’a Samoa” (i.e., “in the way of Samoa”), a credo that emphasizes discipline, responsibility, community … and competitive spirit. As Polamalu once said, “You have to be a gentleman everywhere but on the field.”

And indeed, Ah-Hoy seemed to embody every bit of that. Amid our tour he mentioned that he and his wife and daughter live in a “generational home” with his parents and Lilia’s parents, and as we wheeled around the island his people skills were obvious. If there was a question, he answered it. If somebody needed extra assistance, he provided it. If somebody talked over him, he kept his patience.

But you don’t have to look too hard online to find out what kind of player he was. There’s video, for instance, of a 2015 playoff game in which Kahuku ran the ball on its first 21 offensive plays, en route to a 43-0 victory over Farrington. Ah-Hoy left the game with an ankle injury, but not before piling up 174 yards on 23 attempts.

“My high school team,” he said, “is kind of like the Alabama of Hawaii. We have all of the big kids. We have all of the rugged kids. We just created a package called the elephant package – basically telling the other team we’re gonna line up with all 11 guys on the line: Try and stop us, and if you can’t, we’ll run right over you.”

He ran for 103 yards and four touchdowns in a 39-14 defeat of Saint Louis in the ‘15 state final, capping a 13-0 season in which Kahuku outscored its opponents 536-53. The Red Raiders’ rush/pass ratio was a tidy 536-to-83, with Ah-Hoy accounting for 46 of those pass attempts, and 22 completions.

Not quite two years later, he learned that football did in fact have an expiration date. Somehow he seems to be OK with that – better than most would be, in fact. That too is a tribute to his heritage.

He talked about when Tua Tagovailoa, against whom he once competed, was drafted fifth overall by Miami in 2020 – how Tua made certain to shout out his home island.

“He even said it himself: ‘When I make it, my whole state makes it,’” Ah-Hoy said. “Where I come from, we all make it. Within Hawaii, you’ve got to understand that it’s not just the family who raises him; it’s the village around him that raises him. That word Fa’a Samoa, that’s where it comes from: When one makes it, we all make it.”

For him, that seems to be quite enough. If it took him a while to get there, that’s understandable. But he appears to be there now – embracing what is, as opposed to what might have been. Understanding that not everyone can be part of his high school’s impressive roll call, and that there are other ways one can make an impact.

That’s what lingered, long after he dropped us off at the airport at the end of our tour – how well he had turned the page, and how much he put into a job (or, at least, one of his jobs) that others might approach with far less seriousness.

“Those who grew up in my community, we’re all like this: The best that you can serve others, that brings us joy,” he said, adding that he just wanted to “show off” his island and “spread the culture.”

“The way you want to be treated is how you should treat others,” he said, “and that’s how I approach this job. If I can make an impression on just one person, it makes my day.”

Sept 30, 2017 is just a memory to him now. Not a nightmare. Not a lodestone, weighing him down. Just a day. There have been better ones since, and he left the impression that many more lie ahead.

Another great insight by Gordie Jones, one great writer and one of my favorite friends! Awesome work…per usual .

Much appreciated, Tom. Thanks.

Great story, Gordie. I covered Kesi in high school. I think he carried the ball 39 times in one state championship game. I remember him having that dazed look late in the game after one particularly savage thrust up the middle and booming hit.

If you get a chance, check out my website — BedrockSportsHawaii.com. With your permission, I would like to reprint this article there.

LMK. Aloha, Nick Abramo

Thanks for reading, Nick, and for your kind remarks. And you’re more than welcome to reprint the piece.