Over three decades after Harry Chapman’s death, Stan Gelbaugh still has a copy of a poem given to him by his late football coach at Cumberland Valley High School, someone Gelbaugh calls “probably the most important man in my life, other than my dad.” The poem is entitled “The Man in the Glass,” and its premise is that the person one must please, more than any other, is the one staring back at him in the mirror.

“It’s kind of how I go through life, I guess,” Stan told me over the phone recently.

What he sees looking back at him is a guy who rose from eighth on the quarterback depth chart as a freshman at Maryland to one who started for the better part of his last two seasons. A guy who spent nine years in the NFL, another in the CFL and a pair in the long-defunct World League of American Football (WLAF).

And he sees a cancer survivor.

He’s built a nice life for himself. He is the senior vice president for business development at Kalmia Construction in Beltsville, Md. He and his wife, Denise, have a home not far from his office, but have been riding out the pandemic at their place in Ocean City, Md. He figures they will retire there someday.

“I just turned 58,” he said. “I like to say I’m on the back nine. I can’t quite see the clubhouse from here, but I’ve definitely made the turn.”

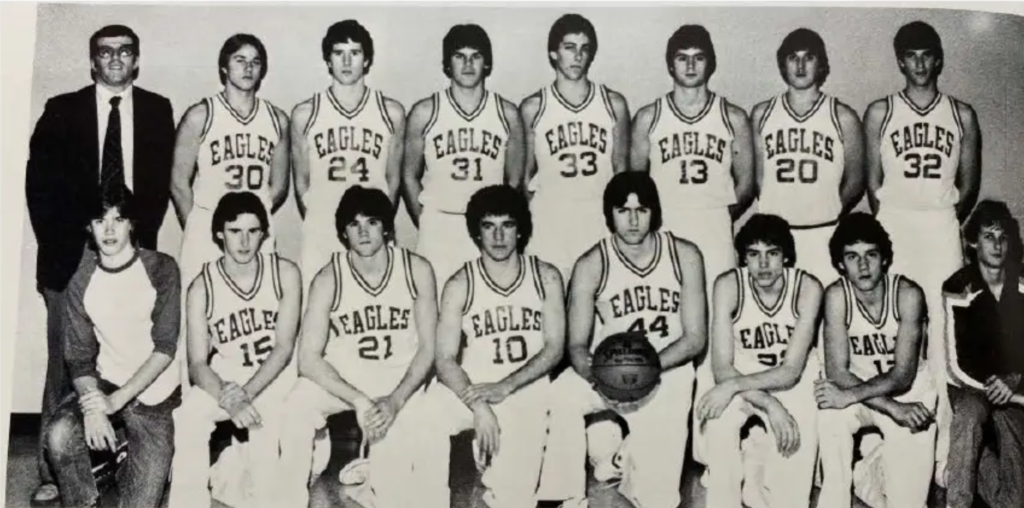

It is much the same for Gelbaugh’s friend and high school classmate, Andy Krosnowski, who with a partner operates a financial planning firm in Falls Church, Va. Their paths, which have crossed occasionally in recent years, were once entwined, as they were teammates in two sports at CV. Gelbaugh played QB and Krosnowski tight end and defensive end on the football team, while Krosnowski played forward and Gelbaugh center on the basketball squad. (Andy, the team captain, is No. 44 in the above photo, while Stan is No. 13.)

Both teams won championships in the old Capital Area Conference their senior year (1980-81), and in hoops the Eagles went 25-6, reached the District Three final (losing 38-34 to Reading) and won the first state-playoff game in program history. That victory total remains a program record.

I covered those teams for the Carlisle paper — it was my first job out of college — and while I can’t quite articulate what compelled me to reach out to Stan and Andy recently, it felt like the right thing to do. Guess I just figured that while it’s never the best thing to live in the past, it doesn’t hurt to visit every now and then.

The last time we had been in each other’s orbit was the night of March 21, 1981, when the Eagles lost to Wissahickon in the second round of states, in a game at William Tennent High School, in Warminster. It had been close throughout, and CV had done a good job defending Wissahickon star Bob Lojewski, a future Big Five Hall of Famer at St. Joe’s. But a guy named Terry Samuels — who was not even on the scouting report, Krosnowski recalled — stepped up with 23 points, and Wissahickon won, 54-46.

I had ridden the bus that night with the team, at the invitation of Eagles coach Jim Dooley — an invitation gratefully accepted, as I was making under $200 a week and could ill afford another tank of gas. So when we parted company early on the morning of March 22 after the four-hour round trip between suburban Harrisburg and suburban Philadelphia, it represented a turning of the page.

I covered a game Stan quarterbacked at Maryland — Penn State’s season-opening 20-18 victory over the Terps in a scalding Byrd Stadium in 1985 — but hadn’t spoken with him or Andy since their high school days. I remembered liking them then, though, and found myself liking them still. Andy does most of his business over the phone and is, unsurprisingly, an engaging guy.

“Your voice,” he told me at one point, “sounds no different than when I met you 40 years ago. And it takes me to a special place and time on that bus.”

Stan, just as charming and a little more self-deprecating, called the passage of four decades “surreal.”

“I don’t feel like I’m almost 60 years old,” he said. “But then, my wife and I have this saying: We get up in the morning and look in the mirror and think to ourselves, ‘That just can’t friggin’ be accurate.’ ”

Then he laughed, something he did often during an hour-long conversation.

If there was a takeaway from all this, it is that high school never ends, in some respects — that a great many of us are sustained by things from those formative years, whether friendships or lessons or memories. They make us who we are, prop us up, propel us forward.

They both remember Chapman’s drive. How he would set up strength and flexibility stations throughout the school’s gym in the summertime, and grade players on how they progressed in their workouts. Gelbaugh was one of the few to ever earn an A-plus, while Krosnowski earned an A. (“Maybe my benchpress was not A-plus or something,” he recalled.) The result, they believe, is that their team was so well-conditioned that it wore opponents down. The Eagles went 10-1 each of their last two seasons, concluding a five-year stretch that saw them go 49-5-1.

They also remember Dooley’s meticulousness. How he would hand out four-by-six index cards to each player, every game day, with a poem about the opponent on one side and an outline of the player’s responsibilities on the other. How he had the Eagles practice against defenders wielding tennis rackets before facing Lebanon 7-footer Sam Bowie in districts in 1978-79. (It didn’t help. Nor did the fact that Dooley stalled in the first quarter, which ended in a 4-4 tie. Lebanon went on to a 45-24 victory.)

Both coaches are gone now. Chapman, a product of the George Chaump coaching tree, succumbed to bone cancer in March 1989, at age 46, having led the Eagles to a 151-48-3 record, five CAC championships, three Mid-Penn Division I titles and two District Three crowns in 18 years. Dooley, a Bronx native whose game-day attire always included saddle shoes, died in 2013 at age 69, when aplastic anemia led to kidney failure. In five coaching stops he accumulated over 700 victories, one of the last in a district championship game while heading Delone Catholic.

Certainly you don’t have to look too hard at Gelbaugh and Krosnowski to see elements of both coaches in them. Krosnowski, who turns 58 on Feb. 2, has completed a triathlon, been part of a tennis team that won a national age-group title and hiked Mt. Kiliminjaro and Mt. Rainier. He has also climbed to Mt. Everest’s base camp. (And forgive him if he has no desire to summit Rainier and Everest, which require technical expertise. “I don’t need to do stuff where you could die,” he said.)

Gelbaugh fashioned that long professional football career, highlighted by his being named WLAF Offensive MVP in the spring of 1990, while playing for the London Monarchs. And if he didn’t achieve great success in the NFL — he appeared in just 20 games over his near-decade in the league — there are memories he holds dear.

None is better than when he came off Seattle’s bench during a Monday Night Football game in 1992 and engineered a fourth-quarter comeback against Denver. First he threw the tying three-yard touchdown pass to Brian Blades on the final play of regulation. Then he drove the Seahawks to the winning field goal in overtime.

“I have (the pass to Blades) on tape so I can watch any time I want,” Gelbaugh said, “but I’ll have to admit there’s dust on it. Nobody else gives a shit at this point.”

Then he laughed again.

He was diagnosed with cancer in the fall of 2019, something, he said, “that sets you back in your chair.” The tumor, called a myxoid liposarcoma, was high on the back of his right leg, and required 30 rounds of radiation. It was successfully removed in January 2020, but the 20-inch surgical wound took far longer to heal; only four months of being hooked up to a wound vacuum remedied that issue.

Certainly the entire ordeal caused him to peer into the mirror once more.

“You look at things in a little different way,” he said, “but the bottom line is … you’ve just got to say, ‘Well you know what? This isn’t getting me. It isn’t my time.’ ”

He had accepted a full ride to Maryland all those years before over Temple, Rutgers and North Carolina State, only to arrive in College Park and find his name No. 8 on the depth chart.

“I think I was more shocked to see that than I was to find out I had cancer,” he said, after rattling off the names of those listed above him, including future pros Boomer Esiason and Frank Reich.

Gelbaugh eventually climbed to the top of the heap. And while he regrets never beating Penn State in his career — and Maryland came close both years he started — he relishes that his final college game was a Cherry Bowl victory over Syracuse, which had pulled his scholarship offer coming out of high school.

As for Krosnowski, he headed off to Lehigh after high school, but was told he had to put on 30 pounds so he could play outside linebacker. His 6-3 frame couldn’t handle the extra weight, and he wound up with various leg-muscle pulls. Worse, he tore a hamstring while water skiing before his sophomore year, and after moving to tight end later in his career suffered a neck injury.

“One thing that’s always bothered me is not having been able to maximize my potential,” he said, describing himself as a “miss-utilized asset.” “But there’s nothing you can do about it. You’ve got to let it go.”

And at the time, he decided, you’ve got to see it through.

“I didn’t want to quit,” he said. “It wasn’t who I was.”

Again, it’s a matter of pleasing oneself, of putting into practice everything you’ve picked up along the way. Which is probably why it felt so good to touch base with the two of them, and understand the paths they have traveled.

“Isn’t it weird?” Krosnowski said as we were wrapping up our conversation. “It was like a crossroads, I guess.”

Gelbaugh signed off in his own way.

“Thanks,” he told me with yet another laugh, “for not being too much of a dickhead to me in the newspaper back then.”

Too much? OK, we’ll put that aside for the time being. Suffice it to say that the two of them have turned out fine. That they have built on the foundation they were once provided. And that neither of them has any trouble looking in the mirror.

Nice story, Gordie. I am borrowing your line (and crediting you) “If there was a takeaway from all this, it is that high school never ends, in some respects — that a great many of us are sustained by things from those formative years, whether friendships or lessons or memories. They make us who we are, prop us up, propel us forward.”

I am forwarding it to several high school friends.

So nice of you to do that, Earle. Thanks so much.

Earl, that was my takeaway also. I’m coaching 5th grade travel boys basketball and I’ve often told them this time and in high school will be some of their best memories. This is the time that really forms young men. Well done, Gordie. Really enjoyed your story. I did not know these individuals well, but after reading your story I feel like I do.

Thanks so much, Eric. They were both good guys, and still are. Would really love to catch up with them face to face, once the pandemic ends.