In the spring of 1975, Matt Brown was deep into his senior year at York Catholic High School and considering places where he might continue his basketball career. Villanova was recruiting him, he recalled over the phone the other day. Seton Hall, VMI and St. Peter’s, too. Maybe a few others. But he was clearly a serious young man with serious ambitions, and to that end he visited West Point.

In the spring of 1975, Matt Brown was deep into his senior year at York Catholic High School and considering places where he might continue his basketball career. Villanova was recruiting him, he recalled over the phone the other day. Seton Hall, VMI and St. Peter’s, too. Maybe a few others. But he was clearly a serious young man with serious ambitions, and to that end he visited West Point.

One problem – there was no head coach.

The guy who had begun recruiting him, Dan Dougherty, had been fired after going 3-22 in 1974-75, and it wasn’t until after Brown paid his visit – there to be shown around by some assistants – that the new guy was hired.

Guy by the name of Mike Krzyzewski.

Brown had no idea who he was, and certainly had no idea how to pronounce his name. (As we all know now, the proper pronunciation is “Coach K.”) And if Brown had any trepidation about the 28-year-old Krzyzewski never having been a college head coach before, he didn’t mention it. Rather, he said, he liked the fact that the new Army boss had graduated from the Academy, Class of 1969, and would know better than anyone the demands placed upon the Cadets. Brown also relished the idea of negotiating a schedule featuring several schools that would join the newly formed Big East in 1979. And the 6-5 guard figured Coach K’s motion offense would be well-suited to his abilities.

One other thing, too.

“I enjoyed structure,” Brown said.

What better place than West Point for that?

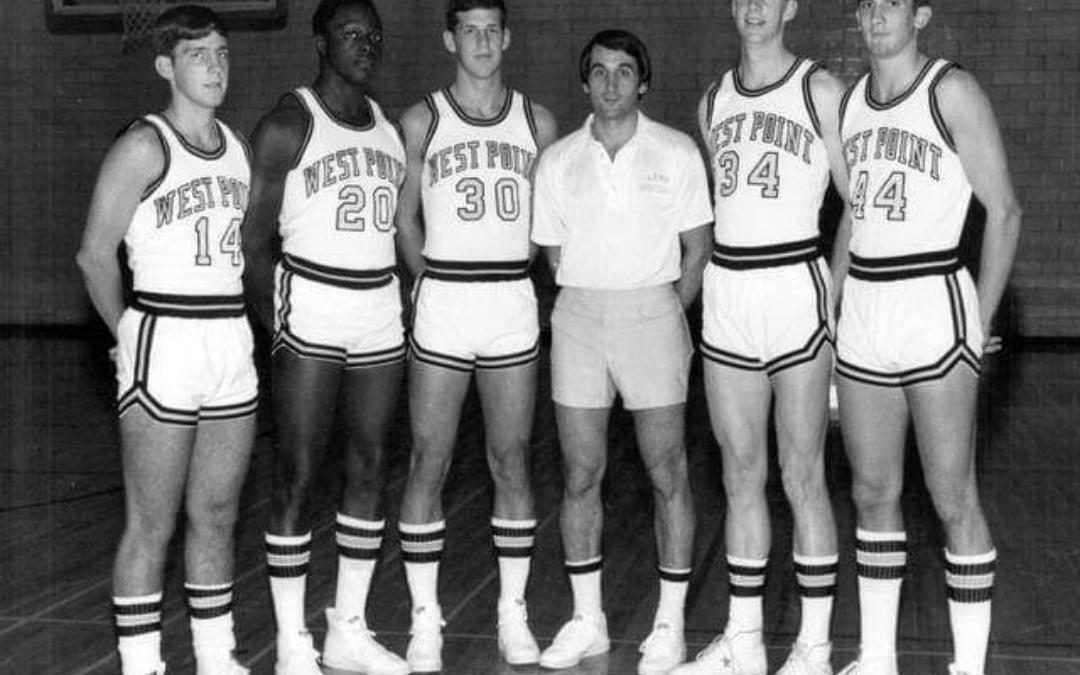

So it was that Brown (No. 30 in the photo atop this post) became the first recruit on Krzyzewski’s first team. To that point in his career he had coached service teams for a few years before spending a single season as a graduate assistant at Indiana under Bob Knight, who had also been his coach at Army.

Challenging as day-to-day life is at West Point, Brown once said that practice was “definitely a break.” Doesn’t mean it was easy, though.

“You needed to come ready to play,” he said, “or you would hear about it.”

He would thrive in Coach K’s crucible, just as Krzyzewski had once thrived in Knight’s, scoring 1,511 points and playing on winning teams the last three of his last four years, including a 20-8 squad in 1976-77 (his sophomore season) and a 19-9 club in ‘77-78. He also built a career upon the structure the Academy provided, spending 28 years in the Army and rising to the rank of colonel before his retirement in 2007. His final assignment was at the Army War College in Carlisle, and he still lives in that community.

He has maintained close ties with the 75-year-old Krzyzewski, who of course followed up his five years at Army with a glittering 42-year run at Duke. Brown, 64, said he sees him two or three times a year. Saw him Tuesday in Pittsburgh, in fact, when he traveled out there for Duke’s rout of a Panthers team coached by ex-Blue Devil Jeff Capel.

It was the last regular-season road game for Krzyzewski, who long ago announced he would be retiring after this season, ending a career that has seen him win more games than anybody else who has ever coached the sport – 1,196 to date. The first 73 came at Army, the first 64 of those with Brown on the roster.

There have also been five national championships at Duke and three Olympic gold medals for Team USA. And another milestone comes Saturday, when Krzyzewski coaches his final home game, against archrival North Carolina. Dozens of former Duke players have been invited back to Cameron Indoor Stadium for the occasion. Brown will not be there, though.

“That’s his show,” he said. “That’s a Duke show. And I fully understand and appreciate that.”

He said he was able to visit with Krzyzewski for 25 minutes at the mid-day shootaround before the Pitt game, as shown in the color photo above. Listened as his old coach said how much he likes the current team, which has fashioned a 26-4 record to date.

If the two of them shared any particularly meaningful moments then (or any other time), Brown wasn’t about to share them in his first conversation with me. Nor would there be any revealing or amusing anecdotes; on that score the old colonel strictly went name/rank/serial number. At the same time he made his respect and admiration for Krzyzewski abundantly clear, saying that electing to play for him was “one of the great decisions of (his) life” and ticking off the reasons he excels as a coach.

The first was, as mentioned, the manner in which he challenges his players.

“A one-hour practice, a two-hour practice – you have to come ready to play for those two hours,” Brown said. “You want to be a better player. You want to be a better teammate.”

It’s a matter of preparation, he said – preparation and execution.

“And,” Brown added, “he also taught us how to have a dream, how to have a vision. And so those three things – preparation, execution and a dream to be better – is what he’s taught me.”

He identifies most with Krzyzewski’s 1985-86 team, which was led by Johnny Dawkins and featured the likes of Tommy Amaker, Mark Alarie, David Henderson and current ESPNer Jay Bilas. That club lost to Louisville in the national final, but in Brown’s mind reestablished Duke’s program, just as the teams on which he played had reestablished Army’s.

When coaching a seasoned team like that ‘85-86 outfit, Krzyzewski tends to be more business-like, less apt to trot out the sort of “rah-rah” (Brown’s phraseology) young clubs require. Practices are shorter and tighter. Everybody knows what the mission is, and how it can be accomplished. There’s no need for any extraneous motivational tactics.

In the twilight of his career, however, he has coached teams laden with one-and-done stars. Every year he has had to reload and recalibrate. He won his last title with such a team in 2015, but has fallen short every year since.

“Obviously the one-and-dones are very, very talented,” Brown said, “but they’ve probably never been pushed, because in high school they dominated or the AAU circuit they dominated. Now they’re up against older men, let’s say, and they’re getting pressed. And how well can they respond?”

His own career, by the way, continues. He plays every other year in the National Senior Games, and finds that he still has a little left in the tank.

“I’m a lot slower, but everything seems to be together,” he said. “You never lose a jump shot.”

He’s no less fascinated to see whether his old coach can nail one last shot, while continuing to relish the one both took all those years ago. The one that found nothing but the bottom of the net.